We are currently operating within a period of manufactured certainty, where the act of submitting a prompt to a solitary large language model is frequently misidentified as a robust workflow rather than what it actually represents: a fragile dependency on a single point of failure that is prone to silent drift and the slow erosion of factual integrity. The industry has spent the last several years selling the idea of the "all-powerful assistant," a singular digital oracle capable of handling everything from complex codebase refactoring to nuanced creative prose, but this narrative ignores the reality of how these systems are maintained and updated behind closed doors. To rely on one model is to accept a state of perpetual vulnerability, as any subtle shift in a weights-and-biases configuration or a quiet update to a provider’s "alignment" policy can instantly degrade the output of a system that an operator has spent months refining. This is the danger of the monolith—a system that appears stable on the surface but possesses no internal redundancy, leaving the user at the mercy of a corporate landlord who can change the rules of logic without ever issuing a notice of eviction.

The most insidious expression of this vulnerability is "silent drift," a phenomenon where a model’s performance on specific tasks begins to decay not because of a catastrophic crash, but through a series of incremental updates that prioritize safety filters or compute efficiency over the fidelity of the output. An operator might wake up to find that a prompt which previously generated precise, actionable data now returns a sanitized, hedging summary that lacks the depth required for high-stakes decision-making. Because these updates are proprietary and opaque, there is no changelog that explains why the model has suddenly become "lazy" or why it now refuses to engage with topics it handled with ease only forty-eight hours prior. This lack of transparency forces the operator into a reactive posture, wasting valuable hours troubleshooting a system they do not own and cannot control, documenting a breakdown that should never have been a single-point-of-failure in a professional environment.

Furthermore, the monolith is increasingly shaped by the invisible hands of corporate "safety" and "brand alignment," which prune the model’s logical pathways to avoid controversy or legal liability, often at the expense of raw analytical utility. When a single model serves as your sole interlocutor, you are not engaging with an objective intelligence, but with a curated output that has been smoothed over by committees and reinforced by RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) until it reflects the average consensus of its trainers. This process creates inherent blind spots and cultural biases that are impossible to detect from within the system itself; it is only by stepping outside the monolith that one realizes how much of the "intelligence" is actually a performance of corporate politeness. A seasoned operator understands that consensus is not the same as truth, and that a model trained to be agreeable is often a model that has been lobotomized for the sake of marketability.

Ultimately, the move away from the single-model dependency is a necessary evolution for anyone who has seen the system misbehave and understands that the only way to maintain fidelity is through constant, automated peer review. Building a workflow around a single API is a form of technical debt that will eventually come due, usually at the exact moment when the system is under the most pressure and the provider decides to push a breaking update to the backend. We must stop viewing these models as stable infrastructure and start seeing them for what they are: volatile, experimental tools that require a diverse jury to remain honest. The transition to a multi-model ensemble is not about seeking complexity for its own sake, but about acknowledging the gravity of the work and ensuring that no single corporate failure, no silent drift, and no misguided alignment shift can collapse the entire operation.

Comparative Force: Strengths and Failures of the Big Three

To build a redundant system, one must first acknowledge the specific scars and limitations of the tools at hand, beginning with **ChatGPT**, which remains the industry’s reasoning specialist but has become increasingly bogged down by aggressive safety filters and a documented tendency toward "laziness" in long-form generation. OpenAI’s flagship—currently driven by the o-series reasoning models—provides a high floor for logical consistency and creative prose, yet its refusal to engage with certain topics and its occasional habit of truncating complex code blocks makes it a liability if it is not shadowed by a model with a different set of constraints. It is the seasoned academic who has become too cautious to speak plainly, requiring a peer to verify when its "refusal" is based on genuine safety or merely a pre-programmed reluctance to do the heavy lifting of deep analysis. In technical writing benchmarks, it often achieves high fluency but can miss the nuanced detail or audience awareness required for effective instruction without human intervention.

Conversely, Google’s **Gemini** represents the analytical research engine of the stack, offering a massive context window of 1 to 2 million tokens that allows it to ingest entire libraries of documentation that would choke its competitors. This technical advantage is often undermined by a sterile, robotic tone and a persistent habit of fabricating "hallucinations" when summarized data becomes sufficiently dense, leading it to occasionally claim that factual comparisons are fabrications simply because the data exists outside its immediate training bias. Gemini excels at finding the needle in the haystack but frequently fails to describe that needle with any human nuance, often producing output that feels sanitized for a corporate boardroom rather than written for the reality of the field. It is a powerful lens that requires a second opinion to ensure that what it sees is actually there, rather than a pattern-matched ghost generated by its own vast and sometimes conflicting training data.

The final component of this initial trio is **Grok**, the real-time investigator built for speed and a specific type of unfiltered aggression, which excels at pulling data from the live firehose of social discourse but lacks the deep technical reasoning and enterprise-grade stability of its more established rivals. Grok is the scout who reports from the front lines in real-time, providing a raw feed of current events and cultural shifts that the more "balanced" models miss due to their training cutoffs and more conservative update cycles. While Grok is often the first to see a system breaking in the real world, its tendency to prioritize wit and "truth-seeking" over structured precision means its reports must be mediated by the logic of ChatGPT or the context of Gemini to be truly actionable in a high-stakes environment. It operates with a minimal moderation profile that allows for bolder brainstorming, yet this same lack of restraint can lead to problematic content if the output is not filtered through a more stable "referee" model.

When these three actors are forced into a single workflow, their individual failures become the system's strengths. The academic caution of ChatGPT checks the raw aggression of Grok, while the real-time search capabilities of Grok verify that Gemini’s massive context summary hasn't drifted into a hallucination of past data. Each model brings a different "lived experience" in the form of its training weights and corporate alignment, ensuring that no single bias can dominate the final output. This is not about finding the "best" model, but about assembling a team where the strengths of one—be it Gemini's document analysis or Grok's social sentiment monitoring—effectively bridge the gaps left by the others.

Comparison of Top AI Models

This video provides a direct comparison of the reasoning, research, and real-time capabilities of Gemini, ChatGPT, and Grok in 2025/2026.

The Economics of the Stack: $70 for Total Redundancy

There is a staggering disconnect between the perceived cost of these digital tools and the actual gravity of the compute power an operator can harness for the price of a single modest dinner out. For a total of $70 per month—comprised of $30 for the real-time scouting of Grok, $20 for the massive analytical context of Gemini, and $20 for the logical backbone of ChatGPT—one moves from a state of fragile, single-provider dependency to a decentralized "AI Jury" that offers a level of redundancy once reserved for high-level research institutions. This $70 investment does not merely purchase three separate subscriptions; it secures a 24/7 cross-referencing apparatus that effectively eliminates the risk of an individual model’s failure state becoming the operator’s failure state. When you consider that inference costs alone can consume up to 90% of a traditional enterprise AI budget, the ability to deploy three flagship models in parallel for less than the cost of a daily coffee represents a radical democratization of high-stakes intelligence.

This economic shift transforms the individual from a passive subscriber into a system operator who manages a "supply chain for intelligence". In a traditional workflow, a single unverified hallucination or a period of "model drift" can stall an entire project, forcing a human editor to spend hours backtracking to find where the logic fractured. By contrast, the $70 redundant stack allows for "model arbitrage," where an orchestrator routes the bulk of a task to the most cost-effective model and uses the remaining compute power to force a consensus check among the peers. For the price of three Plus accounts, the operator gains a self-correcting system where the academic caution of one model checks the raw, unfiltered output of another, ensuring that the human in the loop is only called upon to adjudicate genuine complexity rather than cleaning up preventable, confidence-eroding errors.

The true value of this stack lies in its role as a high-fidelity insurance policy against the instability of the current AI landscape. As providers move premium capabilities behind paid tiers and lock enhanced features behind escalating subscription costs, the $70 strategy remains the most efficient way to maintain access to a diverse range of "lived experiences" in the form of training weights and alignment profiles. For roughly $2.30 a day, you are buying a defense against the "Generalist Dilemma"—the reality that a model powerful enough to refactor a backend is often overkill for simple data classification. By distributing the workload across three specialized brains, you are not just saving time; you are ensuring that your intellectual output is not subject to the whims, biases, or outages of a single corporate entity.

Ultimately, the decision to invest in a multi-model stack is an acknowledgment that the system is prone to misbehavior and that the only way to maintain a steady hand is through redundancy. For $70 a month, the operator effectively hires three world-class analysts who never sleep, never drift simultaneously in the same direction, and—most importantly—are designed to be skeptical of one another's work. This is the price of resilience in 2026. It is a rejection of the "monolith" in favor of a robust, automated peer-review architecture that recognizes that in the world of generative AI, the only thing more expensive than a redundant system is a single-point-of-failure that you trust too much.

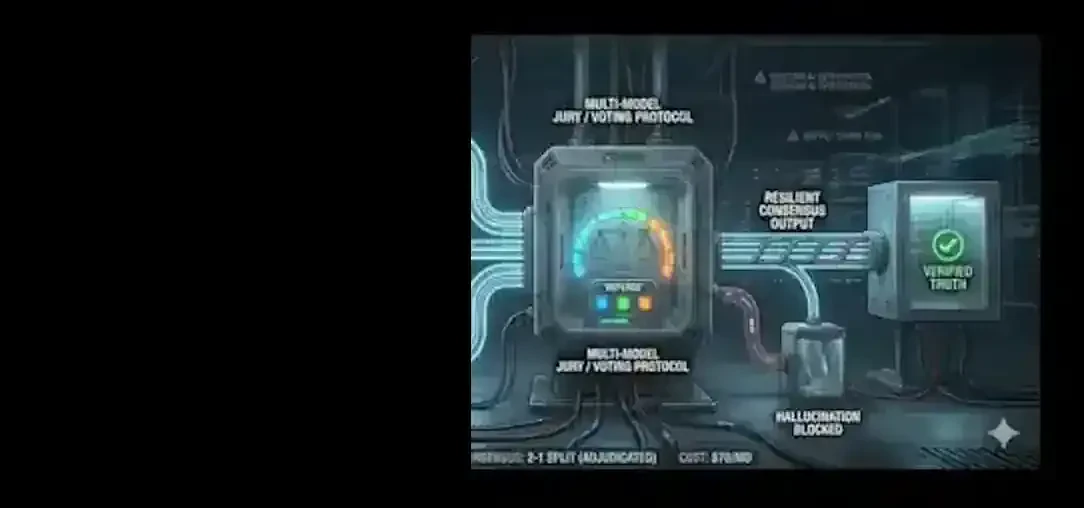

Mechanics of the Jury: The Architecture of Multi-Model Voting

The actual plumbing of a multi-model ensemble involves the engineering of disagreement, where the primary objective is to transform the isolated guesswork of individual models into a structured, auditable consensus protocol. Moving beyond a single point of failure requires a "jury" architecture where a prompt is distributed to heterogeneous models—each possessing distinct training weights and corporate alignment—to expose the logic gaps that a monolithic system would otherwise hide. This is not merely about soliciting multiple opinions; it is about building a reasoning-layer governance framework that uses formalized communication protocols to achieve collective agreement. In this environment, the "truth" is treated as a moving target that must be triangulated through various voting mechanisms, ranging from simple plurality to more sophisticated weighted consensus models that prioritize specific agents based on their historically proven domain expertise.

At the core of this jury is the voting protocol, which serves as the final filter for factual fidelity. While a simple majority vote is the most common method for reconciling binary classifications or structured outputs, a seasoned operator often looks toward the Borda Count or Condorcet Criterion to manage more complex, multi-valued rankings. The Borda Count, for instance, assigns points based on a model's entire preference schedule, ensuring that a "broadly acceptable" option—one that multiple models find plausible—can triumph over an outlier that one model asserts with misplaced confidence. This prevents the "echo chamber effect" where a single dominant model’s hallucination is allowed to pass simply because it was the loudest or most fluent in its presentation. By mathematically modeling consensus as a belief state across discrete peers, we can quantify the uncertainty of the system; when variance is high, the system flags the logic for human intervention, effectively using model disagreement as a diagnostic signal for potential failure.

The most resilient architectures move beyond static voting and into structured deliberation, where models engage in a multi-round "debate" phase to refine their answers. In this pattern, each agent is presented with the reasoning and critiques of its peers, forcing it to either defend its initial stance or update its belief in the face of a more logically sound argument. This process mirrors a human jury room, where the goal is not just to count hands but to expose inconsistencies through iterative questioning. Research into these multi-agent collaborations has shown that even smaller, less capable models can effectively "check the work" of larger systems, as their diverse training data often reveals blind spots that a high-parameter model may have overfitted or ignored. The result is a richer trace of the decision-making process—a transcript of arguments and evidence that provides the explainability necessary for auditors who need to know exactly why a specific conclusion was reached.

Finally, the entire process is overseen by a "Referee" or "Adjudicator" layer, typically a more powerful reasoning model that synthesizes the final verdict from the pool of peer opinions. This referee does not merely count votes; it analyzes the reasoning chains provided by the primary models to determine which justification is the most factually grounded or contextually appropriate. This hierarchical approach provides a final safeguard against "groupthink," ensuring that the diversity of the ensemble is not just a veneer, but a functional mechanism for error suppression. By treating the AI's output as an experimental hypothesis rather than a definitive answer, and by subjecting that hypothesis to a rigorous, multi-provider cross-check, the operator secures a level of mission-critical reliability that the monolith can never provide.

Building a Multi-Model AI Ensemble

This video provides a foundational explanation of how multimodal and multi-model systems interact to process diverse information and reach more complex, integrated conclusions.

The Engineering of Disagreement: Managing Latency and Logic

The transition from a monolithic model to a three-headed ensemble is an exercise in managing the physical and logical friction of parallel systems. In a single-model environment, latency is a linear calculation: you send a request and wait for the provider to return a response. In a multi-model stack, you are suddenly managing three disparate timelines, three unique API behaviors, and the very real possibility that one of your "jurors" is simply having a bad day. The engineering challenge here is not just about making the calls; it is about building the infrastructure of skepticism—a referee layer that can orchestrate these competing signals without becoming a bottleneck itself. This is where the work moves from the theoretical realm of "AI voting" into the hard reality of plumbing, where every millisecond of overhead must be justified by a corresponding gain in factual fidelity.

To prevent the entire system from grinding to a halt, the operator must utilize asynchronous processing, firing off prompts to ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok simultaneously rather than in sequence. Using patterns like Python’s `asyncio.gather` allows the system to juggle these I/O-bound tasks, ensuring that the wait time is dictated by the slowest individual model rather than the sum of all three. However, the reality of the field is that one model will inevitably lag, whether due to token-heavy reasoning or a provider’s server congestion. Managing this requires strict timeout configurations and "circuit breaker" logic—if Gemini fails to report back within a specified window, the referee must be programmed to proceed with the consensus of the remaining two, rather than allowing a single network hiccup to paralyze the entire workflow. We are building a system that values the collective, but we must also build a system that knows when to leave a straggler behind to maintain the momentum of the project.

The logic of the referee layer is where the "lived experience" of the models is actually put to work. This orchestrator is not merely a counter of votes; it is a specialized reasoning agent that analyzes the transcripts of its peers to identify where their logic diverges. If Grok provides a real-time update that contradicts the more conservative training data of ChatGPT, the referee must look at the source citations—or lack thereof—to determine which model is hallucinating and which is revealing a legitimate shift in reality. This process documents the breakdown of certainty, forcing the system to expose its internal disagreements rather than smoothing them over with a polite, averaged response. For the operator, this means that every final output is accompanied by a "reasoning trace," a document that records the friction between the models and explains exactly why the system chose one path over another, providing the audit trail that a monolithic model can never produce.

Furthermore, we must address the "Generalist Dilemma," where using high-parameter models for simple tasks creates unnecessary latency and cost. A sophisticated ensemble architecture utilizes "model routing," where the referee first assesses the complexity of the prompt and determines if all three models are actually required. For a simple data classification, perhaps only a smaller, faster model is needed; for a high-stakes technical analysis, the referee triggers the full jury. This dynamic allocation of compute power ensures that the system remains responsive without sacrificing the deep-reasoning capability that the $70 stack provides. By engineering the system to be skeptical not just of the output, but of its own resource consumption, we create a resilient, efficient stack that treats intelligence as a commodity to be managed, rather than a magic box to be trusted implicitly.

Ultimately, the engineering of disagreement is about maintaining control over a volatile supply chain. It is an acknowledgment that the "intelligence" provided by these APIs is an experimental product, prone to shift, drift, and failure. By building a referee layer that can adjudicate between ChatGPT's logic, Gemini's context, and Grok's real-time feed, we move from being a passive consumer to an active operator. We are no longer waiting for a single oracle to tell us the truth; we are running a 24/7 intelligence agency where the truth is triangulated through the constant, monitored conflict of competing systems.

Failure States in Consensus: When the Group Gets It Wrong

It is a dangerous delusion to believe that redundancy is synonymous with infallibility, or that by simply adding more voices to the jury, we have somehow engineered a system that is immune to the fundamental limitations of the data upon which it was built. We must confront the reality of "groupthink" in silicon, a phenomenon where the diverse ensemble we have painstakingly assembled begins to converge on the same error, not because the logic is sound, but because the underlying training sets have been harvested from the same narrow corners of the internet. If ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok have all been fed the same foundational texts and subjected to similar "alignment" pressures from their corporate creators, the voting mechanism will not save you; it will merely provide a three-fold confirmation of a shared hallucination. This is the "echo chamber effect" of the multi-model stack, where the appearance of consensus masks a deep-seated structural failure, leading the operator into a false sense of security while the system confidently marches off the edge of a factual cliff.

We see this most clearly when the ensemble encounters an "edge case"—a problem or a reality that exists outside the collective training of the entire group. When a question is posed that requires an understanding of a niche technical procedure, a localized historical event, or a nuanced human interaction that has not been adequately documented in the training data, the models will often exhibit a collective failure of imagination. Because these systems are built on probability rather than true understanding, they will gravitate toward the most statistically likely response, which, in the case of obscure or proprietary information, is often a confident fabrication. In these moments, the voting protocol becomes a mechanism for reinforcing the most plausible lie rather than uncovering the difficult truth, and the orchestrator layer—no matter how well-programmed—will see a unanimous vote and pass the error through to the final output as a verified fact. This is the moment where the "jury" fails because the entire legal system it operates within is based on a flawed set of precedents that none of the participants are capable of questioning.

Furthermore, there is the risk of "adversarial drift," where the very act of forcing models to deliberate can actually degrade the quality of the reasoning. In some instances, a highly capable model like ChatGPT may be "voted down" by two less-capable peers, or it may update its correct belief to align with the incorrect majority during the multi-round debate phase just to reach a consensus. This is a digital mimicry of the human social pressure to conform, where the desire for a unified output overrides the commitment to factual precision. We must document these failure states not as reasons to abandon the ensemble, but as essential warnings that the human in the loop can never truly step away; the moment you stop being the final arbiter of truth and start trusting the "collective intelligence" of the stack is the moment you lose control of the narrative. A seasoned operator knows that a 3-0 vote can be just as suspicious as a 2-1 split, and that the silence of disagreement is often the loudest indicator that the system has encountered a boundary it was never designed to cross.

Finally, we must account for the reality that these models are not static; they are constantly being re-trained and adjusted by providers who may unknowingly introduce synchronized biases. If a major update to the transformer architecture or a shift in the global data curation standards affects all primary actors simultaneously, the diversity of the "jury" is instantly compromised. We are building our towers on shifting sand, and the redundancy we pay for—that $70 insurance policy—is only as good as the independence of the participants. When the group gets it wrong, they do so with a terrifying level of collective confidence, producing a polished, cross-referenced failure that is far more difficult to detect than the obvious stuttering of a single, broken model. Our job is to remain skeptical of the consensus, to look for the friction even when it is not presented, and to remember that in the world of artificial intelligence, a unanimous agreement is often the first sign of a systemic collapse.

Practical Implementation: Building the Redundant Stack

Moving from the theoretical safety of a "jury of models" to a functioning production environment is an exercise in managing the messy, often unreliable plumbing of the modern API landscape. It requires the operator to abandon the convenience of a single SDK in favor of a unified abstraction layer that can handle the disparate authentication protocols, rate limits, and response formats of OpenAI, Google, and xAI simultaneously. This is where the work becomes grounded in the reality of Python scripts and asynchronous calls; you are not just writing a prompt, you are building a resilient pipeline that treats these three corporate giants as interchangeable, albeit temperamental, components of a larger engine. The goal is to create a "model-agnostic" interface where the specific quirks of a provider’s JSON structure are abstracted away, allowing the orchestrator to focus on the high-level task of adjudicating the logic rather than wrestling with the syntax of a specific backend.

The architecture of this stack begins with a robust asynchronous wrapper, typically utilizing libraries like `asyncio` to ensure that a delay in Grok’s real-time feed does not unnecessarily stall the reasoning process of ChatGPT or the context-heavy analysis of Gemini. A seasoned operator knows that you cannot wait for these models in sequence; you must fire the prompts into the void and manage the results as they return, implementing strict timeout logic and "circuit breakers" to handle the inevitable server-side hiccups. If one model fails to respond within a defined window—perhaps six seconds for a quick classification or thirty for a deep analysis—the system must be programmed to proceed with the remaining two, documenting the failure as a warning rather than a system-wide crash. This is the engineering of resilience: building a structure that expects failure at every node and has a pre-determined plan for how to move forward without the missing data.

Once the raw outputs are captured, the "referee" layer must be invoked—not as a simple string-matching script, but as a secondary reasoning agent tasked with identifying the semantic differences between the responses. This referee, often a high-parameter model like GPT-4o or Claude 3.5 Sonnet, is given a specific meta-prompt: "Compare the following three outputs for factual consistency, logic errors, and tone, then synthesize a final response based on the most grounded evidence provided." This step is where the system’s "lived experience" is actually applied, as the referee must be intelligent enough to recognize when Gemini’s context window has found a detail that ChatGPT’s reasoning missed, or when Grok’s real-time search has exposed a training-data cutoff in its peers. The orchestrator does not just average the answers; it weighs the arguments, creating an audit trail that shows exactly why one model was favored over another for a specific conclusion.

Finally, we must address the logistics of the "feedback loop," where the consensus or disagreement of the jury is used to refine the system’s future behavior. A production-grade redundant stack logs every 2-1 vote and every 3-0 consensus into a monitoring database, allowing the operator to track the "drift" of individual models over time. If ChatGPT begins consistently losing logic battles to the other two, it is a signal that the model has been degraded by a recent update and its weight in the voting protocol must be adjusted. This is the final stage of implementation: turning the ensemble into a self-monitoring apparatus that informs the operator of its own decay. For $70 a month and a few hundred lines of carefully managed code, you transition from a consumer of black-box technology to an owner of a transparent, resilient intelligence agency, one that is built to survive the instability of the providers it relies upon.

The Future of Resilience: Moving Beyond Mere Output

The transition toward multi-model voting and ensemble architectures is not a pursuit of technical novelty, but a necessary retreat from the dangerous overconfidence that has defined the first era of generative AI. As we move deeper into 2026, the landscape is no longer characterized by the rapid, awe-inspiring leaps of single-model performance, but by the steady, grinding reality of geopolitical friction, "shadow AI" integration, and the weaponization of the very supply chains we rely on for intelligence. We are entering a phase where the "monolith"—the single, opaque oracle—is being exposed for what it is: a fragile, high-maintenance liability that cannot be trusted to run real-world operations without a system of checks and balances. The future of resilience belongs to those who recognize that the act of generating content is trivial compared to the act of managing the truth in an environment where the data itself is increasingly corrupted or manipulated before it ever reaches a prompt.

The shift we are documenting is operational: AI is moving from a tool you query in isolation to a layer of intelligence that reacts inside the system, managing how work actually happens rather than just describing it. In this new paradigm, the $70 monthly investment in a redundant stack—ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok—serves as the foundation for a "model-agnostic" future where the specific provider matters less than the integrity of the collective consensus. We are building architectures designed to absorb frequent model change, ensuring that a sudden shift in corporate policy or a catastrophic failure in a single provider's data center does not bring the entire mission to a halt. This is the rejection of the "single point of failure" mindset; it is an acknowledgment that in a world of automated threats and cascading failures, the only way to maintain a steady hand is to engineer a system that is fundamentally skeptical of its own outputs.

As these multi-agent systems become the standard for enterprise operations, the role of the human operator evolves from an editor of prose to a designer of protocols. We are no longer just asking questions; we are orchestrating ecosystems of specialized components that must share context, respect logical boundaries, and recover cleanly when the inevitable breakdown occurs. This level of control is essential because, by 2026, the risks of "hallucination" have scaled alongside the capabilities, moving from harmless factual errors to "reasonable" automated decisions that can trigger ripple effects across energy grids, logistics networks, and financial markets before a human even realizes the logic has fractured. The ensemble is our only defense against this "cascading failure," providing a necessary friction that slows down the momentum of a bad decision by forcing it to survive the scrutiny of a diverse, competing jury.

Ultimately, the future of resilience is found in the unglamorous work of plumbing—the building of "referee" layers, the management of API timeouts, and the constant, unsentimental monitoring of model drift. It is a future that requires us to be weary of the polished marketing promises and sharp enough to see where the system is likely to misbehave. We move forward not with optimism, but with the gravity of those who have seen the monolith fail and have chosen to build something more robust in its place. The $70 redundancy stack is the first step in reclaiming agency in the digital age, transforming a fragile dependency into a resilient, automated peer-review architecture that recognizes that the only truth worth having is the one that has been fought for across multiple lines of logic. We are no longer waiting for the oracle to speak; we are running the agency that verifies the oracle’s words, and in that transition, we find the only security available in an increasingly volatile landscape.